Asset Manager Capitalism, inequality, and the climate breakdown

“The world’s biggest oil and gas companies have been retreating from their climate commitments and are planning to increase fossil fuel production. They’re doing this in the service of their largest shareholders — firms that most people have never heard of, but which wield enormous power behind the scenes.” - Bill Spence, Professor of Theoretical Physics at Queen Mary University of London, co-author of the report Toxic Investors: The Dirty Dozen’s insatiable drive for oil and gas profits.

Asset Management

Asset management is the practice of increasing total wealth over time by acquiring, maintaining, and trading investments that have the potential to grow in value. [1]

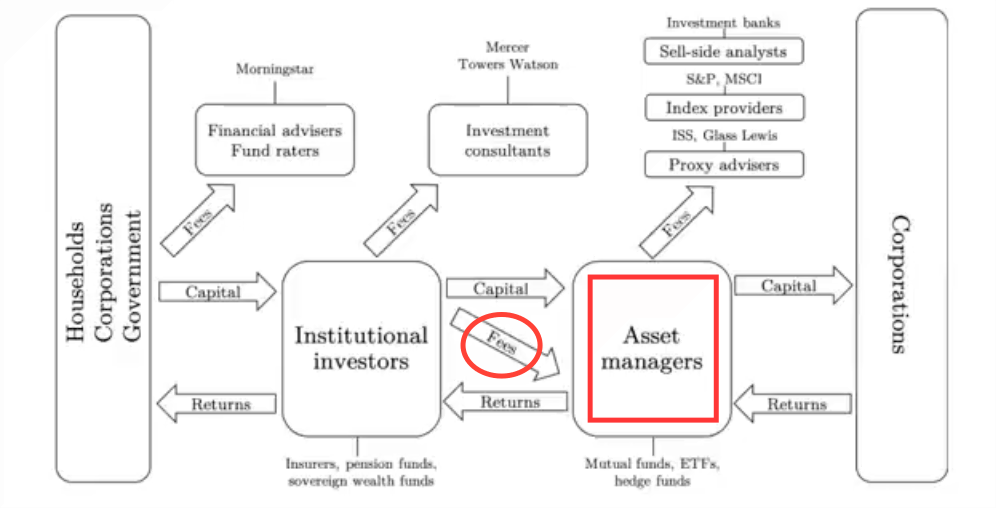

Asset managers are the financial intermediaries who invest on behalf of beneficiaries such as pension holders or wealthy individuals. Despite not owning the shares, asset managers are the agents who hold the voting rights and through proxy voting can shape corporations’ actions on everything from the climate crisis to working conditions. [2]

They are part of the 'Equity Investment Chain' and are fee structured and driven businesses (Figure 2).

Asset Managers make their profits from asset management service fees rather than from investment returns (their income has nothing to do with individual firm performance).

Shares have therefore become assets to generate fees. Fees are a function of the size of the asset footprint. The asset footprint is fueled by ETF sales and booming asset markets. The more shares, the more fees (Professor Mark Blyth explains in the video below).

Asset Manager Capitalism

Asset manager capitalism is the transformation of the global economy from one where the ownership of large corporations was primarily under the control of individual shareholders, insurers and pension funds to one where large corporations are now overwhelmingly under the control of asset managers. [2]

Asset managers are highly concentrated. BlackRock ($9 trillion in assets), Vanguard ($7 trillion) and State Street, the so-called “Big Three” asset managers control 20% of every S&P Dow Jones Indices company and 80% of the Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) market.

Asset managers are also largely 'passive' investors. They diversify their investments across all geographies, industries and asset classes based on pre-determined indices, often from third party providers, rather than on the discretion of portfolio managers looking to ‘beat the market’. This high degree of indexation makes it difficult for investors to exit investments in individual firms if they disagree with a firm's climate strategy or poor labour practices, for example. [2]

Asset manager capitalism has thus developed a structural disincentive for shareholders to be concerned with the actions and performance of companies in their portfolio. Asset managers vote >99% with company management, routinely voting against or abstaining on shareholder resolutions on everything from supply chain deforestation to climate targets, to exorbitant executive pay packets, rather than addressing the systemic risks like the climate crisis or widening inequality. [2] [3] [4]

Government policy and investment

Asset Managers have been nicknamed 'the fourth branch of government' and in the US advise the Federal Reserve which provides asset support programs in times of crisis (GFC and COVID-19), inflating asset prices, lowering the labour share of profit, and diminishing real wage growth. The old 'Revolving Door' of Goldman Sachs staff to the Federal Reserve and Treasury, is now a new 'Revolving Door' from asset manager companies to the National Economic Council, the WEF, and the G30.

Asset management results in wealth preservation for those who already own assets, overriding the original entrepreneurial function and efficient allocation of capital of the market, focusing on shareholder payouts based on corporate debt and undercutting the investment needed in decarbonisation or changes to unsustainable and unjust supply chains. [2]

Inequality

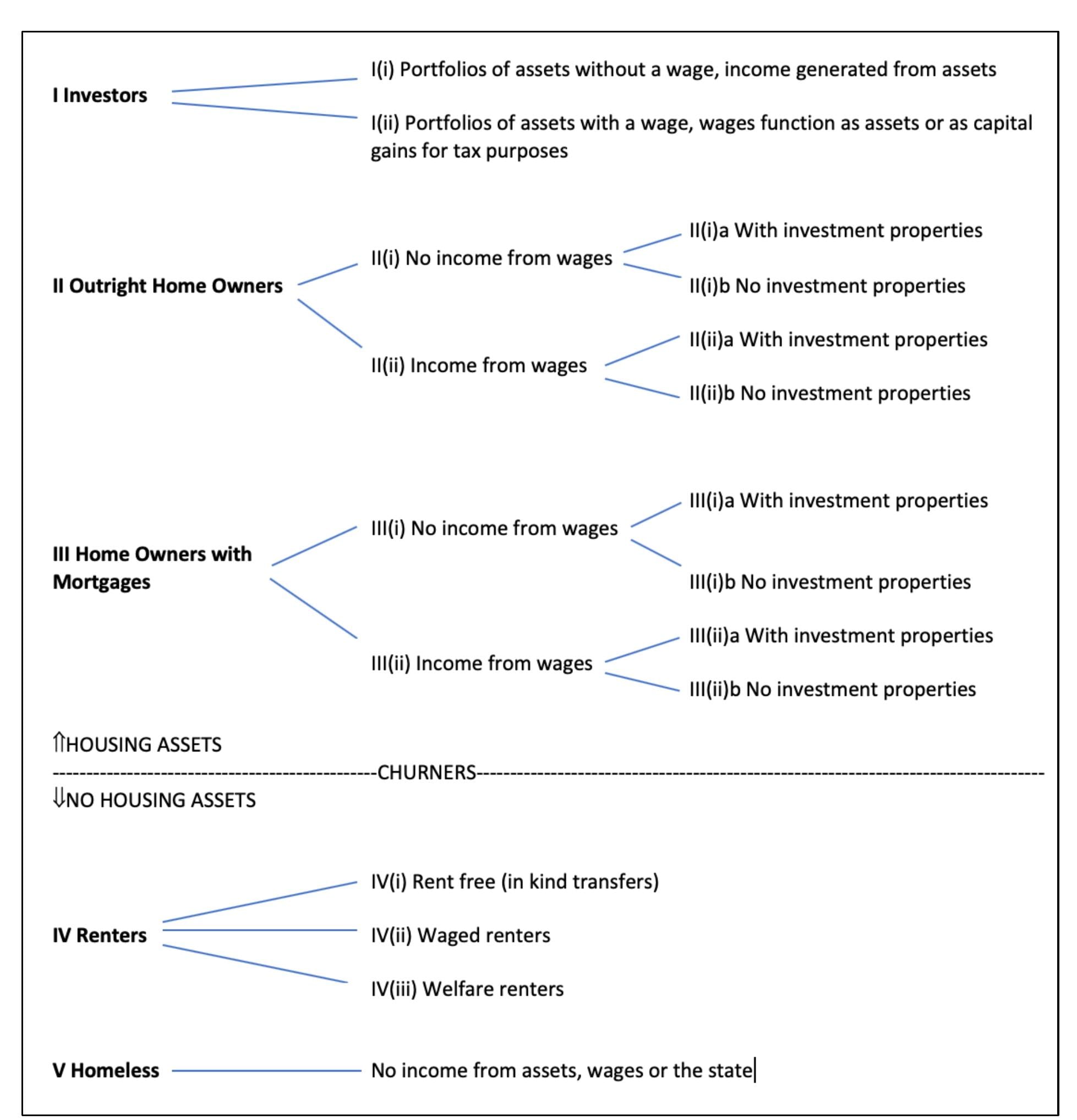

The influence of asset management on government policy is transforming the class structure of our society from one based on career and income, to one based on asset ownership or the lack of asset ownership.

This economic polarisation, and its concomitant political trends will lead to a generation ending up as 'fascists or revolutionaries, one or the other' says Malcolm Harris (2017: 227-8) in his book Kids These Days. [5]

Climate Change

“The concentration of power in a small number of mega-powerful asset managers is the real driving force behind the oil industry’s aggressive push for more oil and gas and more climate breakdown. If we want to tackle climate change, we need to confront those asset managers and take the future of the planet out of their hands.” - Professor David Whyte, Professor of Climate Justice at Queen Mary University of London, co-author of the report Toxic Investors: The Dirty Dozen’s insatiable drive for oil and gas profits.

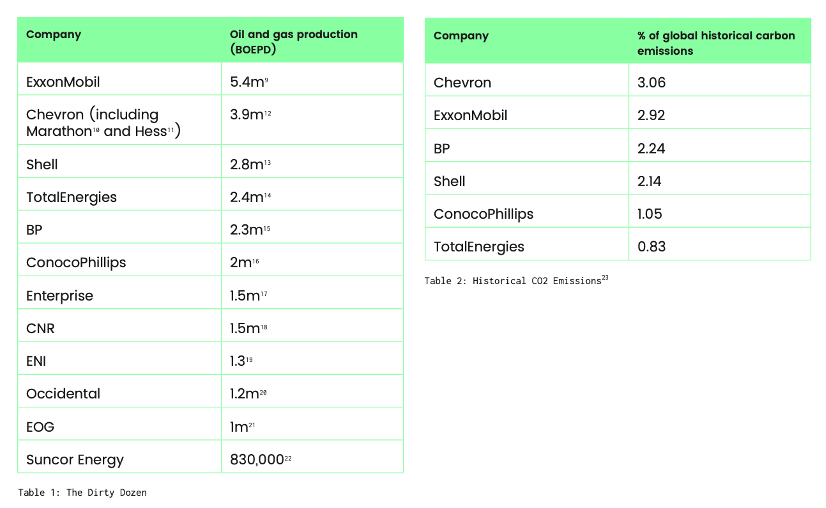

The 'Big Three' Asset Managers control more than 18% of the world’s 12 largest share-owned oil and gas companies' (the 'Dirty Dozen') total shares, a 30% increase since the Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015. Just 25 companies control over 40% of total shares across the 'Dirty Dozen' group.

For fossil fuel expansion and growing inequality to be stopped, we need to overcome these structural barriers to climate action caused by asset managers by designing strategies to challenge and democratise corporate power. [2]

Further information

Adrienne Buller and Ben Braun are interviewed by Grace Blakeley on Asset Manager Capitalism here:

Adrienne has published 2 books:

You can read Lisa Adkins, Melinda Cooper, and Martijn Konings' book here: The Asset Economy

You can read Professor David Whyte and Bill Spence's Queen Mary University of London report here: Toxic Investors: The Dirty Dozen’s insatiable drive for oil and gas profits.

You can read more about Professor Mark Blyth in my previous post.

Notes

[1] Investopedia

[3] Public pension funds consistently applied higher stewardship standards than index funds of comparable size. The largest public pension funds were more willing than mega (> $100B) and large ($10-100B) funds to support shareholder proposals, oppose directors for inadequate board oversight, and vote against say-on-pay proposals. Notably, pension funds in states subject to intense anti-ESG political pressure—including Florida, Ohio, Texas, and North Carolina—still voted against excessive executive compensation at companies with extreme CEO pay ratios, underscoring the salience of inequality-related issues in contexts where stewardship possibilities are otherwise constrained. Many ETFs vote in ways that directly contradict the stewardship priorities of the public pension funds that hold them. For example, CalPERS holds over $15.9 billion in Vanguard’s S&P 500 ETF, which has long voted against all shareholder resolutions and consistently rubber-stamps management proposals. - Accountability in the Boardroom 2025, Majority Action.

[4] Voting power in broad-based equity index funds is highly concentrated among managers of mega-funds that have more than $100 billion in net assets. These funds—managed by Vanguard, BlackRock, Fidelity, and Charles Schwab—are uniquely positioned to curb externality-generating corporate behavior and shape industry standards at scale. Yet across all three core stewardship mechanisms—shareholder proposals, climate-related director elections, and say-on-pay votes—these managers were the least likely to support measures that mitigate system-level risks related to climate change, inequality, and unaccountable technology.

[5] The Asset Economy - Lisa Adkins, Melinda Cooper, and Martijn Konings

[6] Spence, W. and Whyte, D. Toxic Investors: The Dirty Dozen’s insatiable drive for oil and gas profits.